August 2020

My dear graduates of Chaminade, Kellenberg Memorial, and St. Martin de Porres Marianist School,

I have a new hero. His name is Bryan Stevenson, an American lawyer, social-justice advocate, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, and professor at New York University School of Law. Mr. Stevenson has spent his entire adult life fighting injustices in our criminal-justice system. He has worked tirelessly to overturn guilty verdicts based on insufficient evidence, to commute the sentences of prisoners incarcerated on death row, and to represent juveniles who have been made to stand trial as adults and who have too often been sentenced to life in prison for crimes that do clearly not merit so severe a punishment. Despite daunting odds, Mr. Stevenson has met with considerable, albeit hard-won, success. His work has been of particular importance to people of color, many of whom have been convicted of crimes they did not commit or handed stiff sentences significantly beyond the punishment they deserve. Mr. Stevenson is a staunch opponent of the death penalty.

I have never met Bryan Stevenson, but earlier this summer, I finished his book Just Mercy. I suspect many of you have read the book already, or seen the movie (which is definitely on my to-do list for this summer). For those of you who have not, Just Mercy chronicles some of the most important cases in Mr. Stevenson’s 35-plus-year career, most notably, the story of Walter McMillan, a black man who was sentenced to death for a murder he did not commit. For all the bigotry that he has had to endure and all the bias he has had to battle every day, Mr. Stevenson never never succumbs to bitter cynicism. He is, instead, a beacon of hope, determined to build a better society not only for poor people of color, but for Americans of every stripe. At turns both heartbreaking and heartwarming,

Just Mercy is a page-turner. I read it in a single weekend. Just Mercy is also a deeply spiritual book. In a chapter entitled “Broken,” Mr. Stevenson writes candidly about EJI’s growing caseload, his own exhaustion, and his disillusionment with seemingly intractable attitudes regarding race and the criminal-justice system. Mr. Stevenson’s frustration comes to a head when he is unable to obtain a stay of execution for Jimmy Dill, a young man who had been sexually and physically abused throughout his childhood and who suffers from an intellectual disability. Mr. Dill had been accused of shooting someone during the course of a drug deal. The victim did not die at the time of the shooting but became gravely ill several months later, after he had been released from the hospital. When the victim died, in all probability because of inadequate home care, state prosecutors changed the charges against Mr. Dill from assault to capital murder.

Mr. Stevenson recounts Jimmy Dill’s final words to him during a phone conversation immediately before the execution: “Mr. Bryan, I just want to thank you for fighting for me. I thank you for caring for me. I love y’all for trying to save me.” Then, Bryan pours out his own heart and soul in words that crystallize the empathy and humanity that course through every page of Just Mercy: When I hung up the phone that night, I had a wet face and a broken heart. The lack of compassion I witnessed every day had finally exhausted me. I looked around my crowded office, at the stacks of records and papers, each pile filled with tragic stories, and I suddenly didn’t want to be surrounded by all this anguish and misery. As I sat there, I thought myself a fool for having tried to fix situations that were so fatally broken. It’s time to stop. I can’t do this anymore. Bryan continues:

We are all broken by something. We have all hurt someone and have been hurt. We all share the condition of brokenness, even if our brokenness is not equivalent. I desperately wanted mercy for Jimmy Dill and would have done anything to create justice for him, but I couldn’t pretend that his struggle was disconnected from my own. The ways in which I have been hurt -- and have hurt others -- are different from the ways Jimmy Dill suffered and caused suffering. But our shared brokenness connected us.

Paul Farmer, the renowned physician who has spent his life trying to cure the world’s sickest and poorest people, once quoted me something that the writer Thomas Merton said: We are bodies of broken bones. I guess I’d always known but never fully considered that being broken is what makes us human. We all have our reasons. Sometimes we’re fractured by the choices we make; sometimes, we’re shattered by things we would never have chosen. But our brokenness is also the source of our common humanity, the basis of our search for comfort, meaning, and healing. Our shared vulnerability and imperfection nurtures and sustains our capacity for compassion.

We have a choice. We can embrace our humanness, which means embracing our brokennatures and the compassion that remains our best hope for healing. Or we can deny our brokenness, forswear compassion, and deny our own humanity.

I could continue quoting Bryan Stevenson for pages and pages, but I want to address the next point in this month’s reflection, so I will leave you with these excerpts as a sampling of the spirit of Just Mercy. And if I might be so bold, if you haven’t read Just Mercy, do so. You will be truly inspired.

It’s no secret, I suppose, that I write these monthly reflections not only for the spiritual edification of our graduates, but also to encourage a culture of vocations that might prompt young people to consider a vocation to religious life and the priesthood, and, in particular, to the Society of Mary.

And, believe it or not, this morning, as my mind was wandering during Mass (My mind does that far too often!), I started thinking about the connections between Bryan Stevenson’s heroism and my own Marianist vocation.

I usually hesitate to think of a religious vocation in terms of heroism. It’s a proposition, I fear, that is too full of hubris. But in one sense, a religious vocation is about heroism. When I was in high school, some forty-five-plus years ago, I saw many -- in fact, all -- of my Mariainst teachers as heroes. The Brothers were passionate about everything they did. Their dedication went far beyond the hours of 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. spent in the classroom. Marianists like Bro. Larry Syriac and Bro. George Zehnle, Fr. Albert Bertoni and Fr. Ernest Lorfafant formed us intellectually, spiritually, and morally with a dedication and depth that I had never encountered before. Heck, on the weekends and in the summer, they even built twelve new classrooms in a once empty courtyard and transformed a dilapidated estate into a flourishing retreat house that still serves students today.

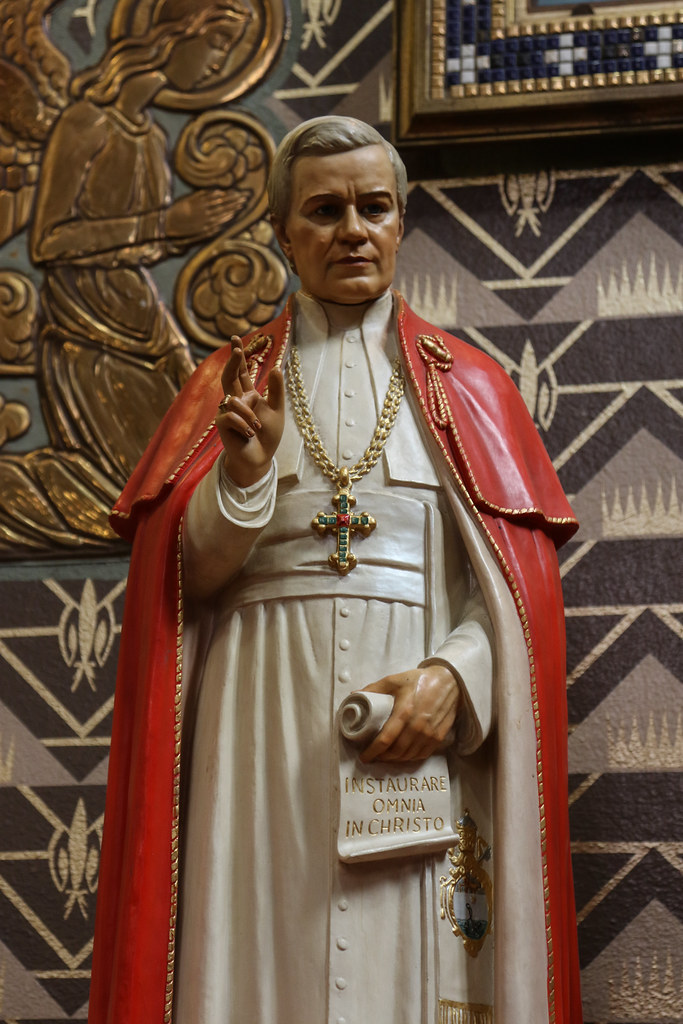

When I joined (at the tender age of seventeen!), I definitely had the sense that I was signing up for a heroic adventure. And all these many years later, Marianist life is still a heroic adventure. We are men on a mission, determined to help make the world a better place by prayer and work, what St. Benedict termed ora et labora. Our prayer is for the salvation of our own souls and for the salvation of the world. Our work is with our students, through education, not simply to impart the knowledge and skills that will enable them to do well for themselves later in life, but, far more importantly, to instill the values and faith that will empower them to make a positive difference for others in this world. In all of this, there is indeed no small degree of heroism. Our heroism, however, is counterbalanced by our brokenness. We are keenly aware of our shortcomings and our limitations. Painfully, we know our failures and our sins. Thankfully, and as Bryan Stevenson so eloquently explains, these remind us of our common humanity. They draw us into a tighter circle of compassion for those whom we serve and those whom we meet in the pages of a book like Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy. Far from dissuading us, our brokenness persuades us all the more of the urgency of our mission. I am more convinced than ever that we need men of faith to carry out our Marianist mission of bringing healing and wholeness to a broken world. We need men who recognize that they can be wounded healers. Blessed Chaminade once said of his fledgling Marianists, “Ours is a great work, a magnificent work.” Thank you, Bryan Stevenson, for reminding me of the heroism of our Marianist life, as we seek nothing less than the healing of a broken world, under the standard of the greatest hero who ever walked the face of the earth, Jesus Christ Crucified and Risen from the dead! On behalf of all my Marianist Brothers, Bro. Stephen Balletta, S.M